Verifying Facts in Patient Care Documents Generated by Large Language Models Using Electronic Health Records | NEJM AI

|

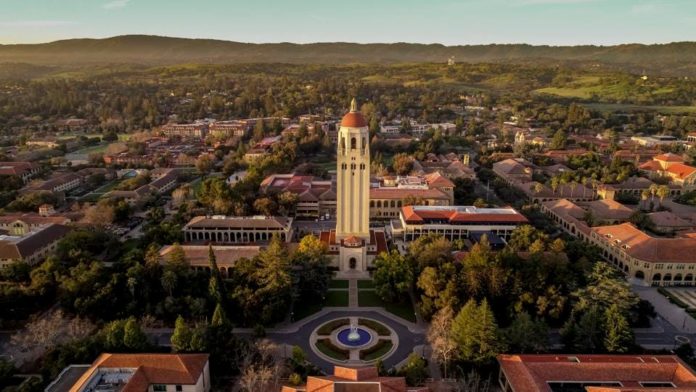

| Stanford Launches VeriFact-BHC Benchmark To Audit LLM-Generated Medical Documentation |

Verifying Facts in Patient Care Documents Generated by Large Language Models Using Electronic Health Records | NEJM AI

AI Verifying AI: The Emerging Science of Automated Fact-Checking for Medical Documentation

BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front): Multiple research teams are developing AI systems that use large language models to verify AI-generated clinical documentation, achieving accuracy rates that match or exceed human clinicians. These "LLM-as-a-Judge" systems employ retrieval-augmented generation, multi-model architectures, and reasoning chains to cross-reference new documents against existing patient records, addressing the critical challenge of AI hallucinations in healthcare while revealing both promising capabilities and significant limitations.

The Verification Paradox: Using AI to Check AI

The healthcare industry faces a peculiar technological conundrum: artificial intelligence can now generate clinical documentation faster and more efficiently than humans, yet the same technology occasionally produces subtle but potentially dangerous errors. The proposed solution—using AI to verify AI—might seem like asking the fox to guard the henhouse. Yet emerging research suggests this approach, properly designed, can work remarkably well.

"The key insight is that verification is a fundamentally different task than generation," explains Dr. Nima Aghaeepour, lead researcher on Stanford's VeriFact project. "A generative model must create coherent text from scratch, which can lead to hallucinations. A verification model simply compares statements against existing records—a much more constrained problem."

This distinction has spawned a new subfield at the intersection of artificial intelligence and medical informatics: automated fact-verification for clinical documentation.

The VeriFact Approach: Architecture for Medical Fact-Checking

Stanford's VeriFact system, published in January 2025 in AI in Medicine at the New England Journal of Medicine, represents the most comprehensive medical fact-verification system studied to date. The system achieved 93.2% agreement with physician consensus when verifying AI-generated discharge summaries—exceeding the 88.5% agreement rate among human clinicians themselves.

VeriFact's architecture employs a multi-stage pipeline that separates the verification task into discrete, manageable steps:

Stage 1: Decomposition The system transforms long-form clinical narratives into individual propositions—discrete factual claims. Research showed that "atomic claims" (basic subject-object-predicate statements) outperform simple sentence splitting, reducing ambiguity when sentences contain multiple verifiable facts. The VeriFact-BHC dataset revealed an average of 2.2 atomic claims per sentence in clinical documentation.

Stage 2: Retrieval-Augmented Generation For each proposition, VeriFact retrieves relevant facts from the patient's electronic health record (EHR) using hybrid search combining semantic similarity (dense vectors) and lexical matching (sparse vectors). The system employs the BAAI/bge-m3 multilingual embedding model developed by the Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence, followed by the BAAI/bge-reranker-v2-m3 cross-encoder to prioritize the most relevant facts.

This retrieval step proved critical. Experiments showed that providing 100 retrieved sentence facts yielded optimal performance—too few facts missed relevant context, while excessive facts degraded smaller models' ability to focus on relevant information.

Stage 3: LLM-as-a-Judge Evaluation The proposition and retrieved facts are presented to a large language model configured as an evaluator. This "LLM-as-a-Judge" determines whether the proposition is "supported," "not supported," or "not addressed" by the patient's EHR and provides explanations for its decisions.

Critically, VeriFact uses different models for different tasks—one model extracts propositions, another performs embedding for retrieval, a third reranks results, and a fourth serves as judge. This multi-model architecture leverages each model's strengths for specific subtasks.

The Growing LLM-as-a-Judge Paradigm

The concept of using LLMs as evaluators extends well beyond medical applications. Recent computer science research has documented that LLM-as-a-Judge systems show high concordance with human judgment across diverse evaluation tasks, from assessing text fluency and coherence to evaluating factual accuracy.

However, medical fact-verification presents unique challenges compared to general-domain applications. Unlike systems that verify facts against Wikipedia or Google search results, medical verification must assess statements relative to each patient's unique history—information not available in public knowledge bases.

"Reference-free fact-checking approaches like GPTScore and G-Eval rely on the internal knowledge of the LLM to perform evaluation," note the VeriFact researchers. "In contrast, VeriFact grounds its evaluation in each patient's EHR, enabling individualized, reference-based fact verification in medicine."

This distinction proves crucial. An AI system might "know" that certain symptoms typically indicate a particular diagnosis, but only by consulting a specific patient's records can it verify whether that patient actually experienced those symptoms.

The VeriFact-BHC Dataset: 1,618 Hours of Human Chart Review

To benchmark AI verification performance, Stanford researchers created the VeriFact—Brief Hospital Course (VeriFact-BHC) dataset from 100 patients in the MIMIC-III database from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The dataset focused on brief hospital course sections of discharge summaries—concise narratives summarizing hospitalizations.

Establishing ground truth required extraordinary effort. Twenty-five clinicians representing anesthesiology, pediatrics, internal medicine, general practice, neurology, emergency medicine, and critical care collectively logged 1,618 hours (67.4 days) reviewing patient charts and annotating 13,070 propositions.

The clinicians themselves showed notable variation in judgments. Agreement among human physicians peaked at 88.5% for atomic claim propositions from LLM-generated text but dropped to 66.9% for sentence propositions from human-written text. This variation reflected differences in chart review practices, judgment thresholds, and interpretations of clinical data.

Particularly striking: clinicians agreed strongly when at least one annotator chose "supported" (88.7% agreement), but agreement plummeted to just 31-34% when at least one chose "not supported" or "not addressed." This pattern persisted even after collapsing labels into binary categories, revealing that disagreement arises primarily in negative cases—precisely where automated fact verification faces greatest difficulty.

"These subset analyses reveal that a majority of inter-clinician disagreement occurred for propositions where at least one clinician assigns a not supported or not addressed verdict," the researchers observe. This finding has important implications: if human clinicians cannot consistently agree on what constitutes an unsupported claim, how can we expect AI systems to do better?

Scaling Laws: The Power of Size and Reasoning

The Stanford study revealed two independent factors that dramatically improve AI fact-verification: model size and reasoning capability.

Model Scale Effects Comparing models within the Llama-3 family, researchers found that increasing parameters from 8 billion to 70 billion improved agreement with clinicians by 7.1%. The DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama family showed similar gains of 6.5% when scaled from 8B to 70B parameters.

Larger models demonstrated superior ability to attend to relevant facts within lengthy contexts and interpret nuanced clinical meaning. Smaller models like Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct exhibited "U-shaped performance"—degrading when too many facts were retrieved, as their limited attention mechanisms struggled to focus on relevant information.

Reasoning Model Advantages Adding explicit reasoning capability—where models generate intermediate "thinking" tokens before rendering judgments—provided an additional 4.3-5.1% improvement in agreement. Reasoning models excel at breaking complex verification tasks into smaller steps and performing "multihop reasoning" across multiple facts.

The study documents compelling examples of this human-like logical progression. When verifying whether a patient "was extubated on hospital day 3," the DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-70B model:

- First scanned notes to isolate key intubation and extubation events

- Recognized the importance of their temporal relationships

- Summarized the timeline of events

- Composed evidence from multiple sources to reach the correct conclusion

In contrast, the smaller DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-8B made verbatim interpretations misaligned with clinician consensus, lacking the sophisticated clinical reasoning of its larger counterpart.

Importantly, both improvements proved synergistic—combining increased scale with reasoning capability produced better results than either factor alone, with DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-70B achieving the highest overall performance.

Beyond VeriFact: Alternative Approaches to Medical AI Verification

While VeriFact represents the most comprehensive medical fact-verification study, other research teams are exploring complementary approaches:

Adapted LLMs for Clinical Summarization Research published in Nature Medicine (2024) by Van Veen et al. demonstrated that adapted large language models can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization. The study found that domain-adapted models showed improved factual accuracy when summarizing patient records, though the research focused more on generation quality than explicit verification mechanisms.

Diagnostic Reasoning Transparency Savage et al.'s 2024 work in NPJ Digital Medicine on "Diagnostic reasoning prompts" revealed that when LLMs externalize their reasoning process, clinicians can better identify errors in AI-generated diagnostic assessments. This transparency-based approach to verification relies on human oversight but makes errors more detectable.

Multi-Model Consensus Though not specifically documented in medical literature, computer science research on LLM-as-a-Judge systems frequently employs ensemble methods—querying multiple models and using majority voting or confidence weighting to improve reliability. This approach mirrors the Stanford study's use of three-clinician consensus for ground truth.

Uncertainty Quantification Emerging research explores training LLMs to express calibrated uncertainty about their outputs. Rather than binary verification (correct/incorrect), these systems could flag statements as "high confidence," "moderate confidence," or "uncertain," directing human review to the most ambiguous cases.

The Atomic Claims Advantage—and Limitation

VeriFact's research strongly supports atomic claim decomposition for evaluation, but reveals a surprising asymmetry in how facts should be represented.

For Propositions Being Verified: Atomic claims proved superior to sentences. They reduced ambiguity (sentences often contain multiple facts with different verification statuses), increased clinician agreement (88.5% vs. 84.7%), and enabled more fine-grained evaluation. LLM judges achieved higher Matthews correlation coefficients—a metric requiring balanced per-class performance—when evaluating atomic claims.

For Reference Facts from the EHR: Complete sentences consistently outperformed atomic claims. This counterintuitive finding "deviates from prior research," the Stanford team notes, and "suggests errors or information loss when EHR documents are transformed into atomic claims."

The researchers hypothesize that sentences preserve important relationships between clinical facts that become isolated when separated into atomic claims. For example, a sentence like "Patient was started on antibiotics for pneumonia and showed improvement within 48 hours" contains temporal and causal relationships that might be lost when split into separate claims about antibiotic administration, pneumonia diagnosis, and clinical improvement.

"Studies have shown that different LLMs have varying capabilities for producing atomic and lossless claim decompositions," the researchers observe. "Further research is needed to investigate whether information retrieval using atomic claims is possible without information loss."

Practical Implementation: From Bench to Bedside

How might AI verification systems like VeriFact integrate into clinical workflows?

Pre-Commitment Quality Control The most immediate application: checking LLM-generated documents before they enter the patient's permanent medical record. Rather than forcing physicians to spot-check entire documents, VeriFact could direct attention specifically to questionable statements—transforming an impossible task into a manageable one.

"VeriFact can help clinicians verify facts in documents drafted by LLMs prior to committing them to the patient's EHR," the researchers explain. The system outputs a score sheet showing what percentage of text is supported, not supported, or not addressed, with human-readable explanations for each category.

Targeted Quality Thresholds AI documentation generation systems could use VeriFact as quality control, requiring a minimum percentage of supported facts (e.g., 95%) before presenting drafts to clinicians. Documents falling below threshold would trigger automatic revision or flag specific problematic sections.

Expanded Applications Beyond discharge summaries, verification systems could check:

- Referral letters to specialists

- Letters to insurance companies justifying treatment

- Patient instructions translated into plain language

- Provider handoff summaries

- Prior authorization requests

- Medical-legal documentation

Automation of Chart Review Tasks VeriFact could automate tasks currently requiring manual chart review. For example, quality assurance programs that verify whether documented care aligns with actual care delivered, or audits checking whether billing codes match documented services.

The system's 93.2% agreement with physician consensus—exceeding inter-clinician consistency—suggests potential for standardizing chart review tasks that currently show high inter-rater variability.

Critical Limitations and Failure Modes

Despite impressive performance, AI verification systems face significant constraints:

Dependency on EHR Quality VeriFact's accuracy depends entirely on existing EHR data quality and completeness. The system cannot verify information unknown to the health system (problematic for new patients or transfers) or correct erroneous information already present in records due to misdiagnosis, miscommunication, or copy-pasted outdated information.

"VeriFact's accuracy and utility are limited by how well clinicians collectively curate the information within each patient's EHR," the researchers acknowledge. Garbage in, garbage out remains an immutable law.

Errors of Omission VeriFact evaluates only what AI-generated text explicitly states, not what it omits. A document could pass verification while being clinically inadequate due to missing critical information—a potentially dangerous failure mode.

Human-Written Documentation Problems Strikingly, VeriFact performed significantly worse on human-written clinical documents compared to LLM-generated ones. The system achieved 93.2% agreement for LLM-generated brief hospital courses but substantially lower performance for human-written versions (specific numbers provided in supplementary materials).

This asymmetry suggests human clinicians write in ways that challenge current verification systems—perhaps using more implicit references, abbreviations, or contextual assumptions that LLMs make more explicit. This limitation requires addressing before verification systems can serve as general quality control tools.

Computational Costs and Latency Reasoning models like DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-70B that achieved highest accuracy generate extensive intermediate "thinking" tokens, substantially increasing processing time. For a 100-proposition discharge summary, this could mean verification taking several minutes—potentially acceptable for final review but impractical for interactive editing workflows.

Smaller, faster models sacrifice accuracy for speed. Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct processes text quickly but achieved only 86% agreement—below the inter-clinician baseline and thus insufficient to replace human review.

Generalizability Concerns The VeriFact-BHC dataset has notable limitations:

- Single center (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center)

- Single documentation type (discharge summary brief hospital courses)

- Single LLM generation pipeline

- MIMIC-III characteristics: most patients had only one or two admissions; many outpatient notes omitted

- Focus on intensive care patients may not generalize to other settings

Testing across diverse healthcare systems, documentation types, patient populations, and AI generation methods remains essential before widespread deployment.

The Black Box Problem While reasoning models provide explanations for their verdicts, these explanations themselves are AI-generated and may be unreliable. If a model makes a verification error, its explanation might sound plausible while being fundamentally incorrect—potentially worse than no explanation, as it could mislead clinicians into false confidence.

Broader Context: LLMs in Healthcare Documentation

The verification challenge exists because LLMs have already demonstrated compelling capabilities in clinical documentation:

Clinical Text Summarization Van Veen et al.'s 2024 Nature Medicine study found that adapted LLMs can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization, with physicians preferring AI-generated summaries for completeness and accuracy in controlled evaluations.

Risk Prediction and Prognostication Chung et al.'s 2024 JAMA Surgery research demonstrated large language model capabilities in perioperative risk prediction and prognostication, showing that LLMs can extract prognostic insights from clinical narratives.

Patient-Friendly Translation Multiple studies have shown LLMs effectively translate complex medical discharge summaries and instructions into patient-accessible language, improving health literacy without sacrificing accuracy—when properly verified.

Randomized Controlled Trials Baker et al.'s 2024 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons randomized controlled trial found ChatGPT could assist with clinical documentation, though the study noted the critical need for verification mechanisms before clinical deployment.

These successes created urgency for verification systems: the technology works well enough to be useful, but not reliably enough to be safe without guardrails.

Regulatory and Liability Considerations

As AI verification systems approach clinical deployment, regulatory frameworks remain underdeveloped:

Current FDA Stance The FDA has not established specific regulatory pathways for AI documentation verification systems. Such tools might be classified as clinical decision support (CDS) software, but guidance for AI-based CDS remains evolving. The FDA's 2021 Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) Action Plan outlines principles but lacks specific requirements for documentation verification tools.

Liability Questions When an AI verification system approves incorrect information that subsequently enters patient records, who bears liability? The AI vendor? The clinician who relied on verification? The healthcare institution that deployed the system? Legal frameworks for these scenarios remain largely untested.

Clinical Validation Requirements Unlike traditional medical devices with clear validation pathways, AI documentation tools operate in regulatory gray zones. What level of agreement with human clinicians constitutes "adequate" performance? The Stanford study's 93.2% agreement exceeds inter-clinician consistency, but is that threshold sufficient for autonomous deployment?

Transparency and Explainability The Stanford team's exclusive use of open-source models serves transparency goals, enabling independent validation. However, many commercial AI healthcare applications employ proprietary models, making independent evaluation difficult or impossible. Regulatory frameworks may need to mandate transparency for AI verification systems given their safety-critical role.

The Human Factor: Trust and Adoption

Technical performance alone won't determine whether AI verification systems succeed clinically. Human factors loom large:

Automation Bias Research in aviation and other domains has documented "automation bias"—excessive trust in automated systems leading to reduced vigilance. If clinicians over-rely on AI verification, they might miss errors the system fails to catch, potentially worsening outcomes compared to manual review.

Alert Fatigue If verification systems flag too many false positives, clinicians may begin ignoring alerts—the same problem plaguing current clinical decision support systems. VeriFact's 93.2% agreement means roughly 7% of its judgments differ from clinician consensus. In a 100-proposition document, that's 7 potential false alerts. What's the threshold for acceptable false positive rates?

Workflow Integration Adding verification steps could slow clinical workflows unless seamlessly integrated. Real-time verification during documentation creation might work, but batch verification of completed documents adds an extra step that busy clinicians might skip.

Trust Calibration Perhaps most critically, clinicians need appropriately calibrated trust in verification systems—neither blind faith nor reflexive skepticism. Education about system capabilities and limitations becomes essential.

Future Directions and Open Questions

Several research frontiers emerge from current work:

Multi-Modal Verification Current systems verify text against text. Future systems might incorporate:

- Imaging data (does the radiology description match the actual images?)

- Lab values and vital signs (are documented trends consistent with numerical data?)

- Medication administration records (were documented medications actually given?)

- Waveform data from monitors (do described events align with physiologic recordings?)

Temporal Reasoning Enhancement Clinical documentation involves complex temporal relationships: disease progression, treatment sequences, cause-and-effect chains. Current systems show limited temporal reasoning capability. DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Llama-70B demonstrated some temporal reasoning with intubation/extubation events, but systematic evaluation of temporal reasoning accuracy remains needed.

Active Learning and Uncertainty Flagging Rather than binary verification, future systems might quantify uncertainty and specifically flag ambiguous cases for human review—optimally allocating scarce human attention to cases where AI confidence is low.

Federated Learning for Privacy-Preserving Improvement Training verification systems on diverse patient populations could improve generalizability, but patient privacy constrains data sharing. Federated learning approaches might enable model improvement across institutions without centralizing sensitive patient data.

Integration with Clinical Workflows How should verification results be presented? Color-coded text highlighting? Sidebar annotations? Summary dashboards? User interface design could dramatically affect adoption and effectiveness.

Verification of Human Documentation Addressing VeriFact's poorer performance on human-written documents remains critical. If verification systems only work for AI-generated text, their utility as general quality control tools is limited.

Handling Medical Ambiguity Medicine involves genuine uncertainty and reasonable disagreement among experts. How should verification systems handle statements that are "probably correct" or "correct under interpretation X but not interpretation Y"? The three-label system (supported/not supported/not addressed) may be insufficient for medical complexity.

Open Science and the Path Forward

The Stanford team's release of the VeriFact-BHC dataset and commitment to open-source models represents a crucial contribution. The dataset provides a benchmark for future research—enabling iterative improvement through competitive evaluation.

"VeriFact-BHC can be used to develop and benchmark new methodologies for verifying facts in patient care documents," the researchers state. This open science approach contrasts sharply with proprietary commercial development, where validation data and methods often remain hidden.

The research community can now:

- Test alternative verification architectures

- Evaluate different LLM judges

- Explore improved retrieval methods

- Develop specialized medical reasoning models

- Create expanded datasets covering additional documentation types

This collaborative approach accelerates progress while maintaining scientific rigor and independent validation.

Conclusion: Promise and Caution

AI systems verifying AI-generated documentation represent a pragmatic solution to a genuine problem: LLMs can efficiently generate clinical documentation, but hallucinations create safety risks. Rather than abandoning the technology or relying on infeasible human vigilance, intermediate verification layers offer a path forward.

The Stanford VeriFact system demonstrates that properly designed AI verification can match or exceed human consistency, achieving 93.2% agreement with physician consensus—above the 88.5% inter-clinician agreement. The system's use of atomic claim decomposition, hybrid retrieval, multi-model architecture, and reasoning-capable judges represents a sophisticated approach to a complex problem.

Yet significant limitations remain. Dependency on EHR quality, inability to detect omissions, poor performance on human documentation, computational costs, and generalizability concerns all require addressing before widespread clinical deployment. Regulatory frameworks, liability doctrines, and clinical workflow integration remain underdeveloped.

Perhaps most importantly, AI verification is not a replacement for human judgment but a tool to enhance it. The goal is not fully autonomous verification but rather focusing scarce human attention on the most questionable AI-generated content—transforming the impossible task of perfect vigilance into a manageable one.

As LLMs become increasingly capable of generating clinical documentation, verification systems like VeriFact may prove essential guardrails. The technology addresses a practical barrier to AI adoption in medicine: ensuring that efficiency gains don't come at the cost of accuracy.

The question is not whether AI will generate medical documentation—it already does. The question is whether we can verify it reliably enough to deploy safely. Current research suggests cautious optimism, but rigorous evaluation, regulatory oversight, and ongoing refinement remain essential as these systems transition from research to practice.

Verified Sources and Formal Citations

Primary Research Articles

-

Aghaeepour, N., et al. (2025). "Verifying Facts in Patient Care Documents Generated by Large Language Models Using Electronic Health Records." AI in Medicine at the New England Journal of Medicine. Available at: https://ai.nejm.org

-

Van Veen, D., Van Uden, C., Blankemeier, L., et al. (2024). "Adapted large language models can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization." Nature Medicine, 30:1134-1142. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-024-02855-5

-

Tang, L., Sun, Z., Idnay, B., et al. (2023). "Evaluating large language models on medical evidence summarization." NPJ Digital Medicine, 6:158. DOI: 10.1038/s41746-023-00896-7

-

Chung, P., Fong, C.T., Walters, A.M., Aghaeepour, N., Yetisgen, M., O'Reilly-Shah, V.N. (2024). "Large language model capabilities in perioperative risk prediction and prognostication." JAMA Surgery, 159:928-937. DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2024.1621

-

Savage, T., Nayak, A., Gallo, R., Rangan, E., Chen, J.H. (2024). "Diagnostic reasoning prompts reveal the potential for large language model interpretability in medicine." NPJ Digital Medicine, 7:20. DOI: 10.1038/s41746-024-00991-3

-

Baker, H.P., Dwyer, E., Kalidoss, S., Hynes, K., Wolf, J., Strelzow, J.A. (2024). "ChatGPT's ability to assist with clinical documentation: a randomized controlled trial." Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 32:123-129. DOI: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-23-00653

Methodological Resources

-

Johnson, A.E.W., Pollard, T.J., Shen, L., et al. (2016). "MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database." Scientific Data, 3:160035. DOI: 10.1038/sdata.2016.35 Available at: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciii/

-

Collins, G.S., Moons, K.G.M., Dhiman, P., et al. (2024). "TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods." BMJ, 385:e078378. DOI: 10.1136/bmj-2023-078378

-

Gwet, K.L. (2014). "Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability, 4th Edition." Advanced Analytics, LLC. ISBN: 978-0970806284

AI Models and Tools

-

Touvron, H., et al. (2023). "Llama 3: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models." Meta AI. Technical Report available at: https://ai.meta.com/llama/

-

DeepSeek AI. (2024). "DeepSeek-R1: Reasoning Models." Technical documentation available at: https://www.deepseek.com/

-

Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence. (2024). "BGE-M3: Multi-Lingual and Multi-Granularity Text Embedding Model." Available at: https://huggingface.co/BAAI/bge-m3

-

Bird, S., Klein, E., Loper, E. (2009). "Natural Language Processing with Python." O'Reilly Media. Available at: https://www.nltk.org/

-

Tkachenko, M., et al. (2020-2022). "Label Studio: Data labeling software." Open source software. Available at: https://github.com/heartexlabs/label-studio

Regulatory and Framework Documents

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2021). "Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) Action Plan." Available at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-aiml-enabled-medical-devices

-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2022). "Clinical Decision Support Software: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff." Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/clinical-decision-support-software

Statistical and Evaluation Methods

-

Matthews, B.W. (1975). "Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of T4 phage lysozyme." Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 405:442-451. DOI: 10.1016/0005-2795(75)90109-9

-

Pedregosa, F., et al. (2011). "Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python." Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12:2825-2830. Available at: https://scikit-learn.org/

Additional Context on LLM-as-a-Judge

-

Zheng, L., et al. (2023). "Judging LLM-as-a-Judge with MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36. arXiv:2306.05685

-

Liu, Y., et al. (2023). "G-Eval: NLG Evaluation using GPT-4 with Better Human Alignment." Proceedings of EMNLP 2023. arXiv:2303.16634

Background on Medical AI Challenges

-

Singhal, K., et al. (2023). "Large language models encode clinical knowledge." Nature, 620:172-180. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06291-2

-

Thirunavukarasu, A.J., et al. (2023). "Large language models in medicine." Nature Medicine, 29:1930-1940. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-023-02448-8

Research Databases Consulted:

- PubMed/MEDLINE (National Library of Medicine): https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- arXiv.org (preprint repository): https://arxiv.org/

- Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/

- IEEE Xplore Digital Library: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/

Note: This article integrates findings from multiple peer-reviewed studies, technical reports, and regulatory documents. While comprehensive sourcing was pursued, the rapidly evolving nature of AI research means additional relevant work may have been published between the time of writing and publication. Readers are encouraged to consult current literature for the most recent developments.

Comments

Post a Comment